A Good Day for a Walk in the Woods

January 19, 2017

Not since the Civil War has an American presidential Inauguration Day been so fraught with fear and dread (on February 23, 1861, Abraham Lincoln traveled to his inauguration under military guard, arriving in Washington, D.C., in disguise). The incoming president is the most unpopular of any to assume office since modern polling began. In a single news cycle this past week he managed to alienate allies throughout an entire continent (Europe) during a brief break in a string of petulant tweets intended to persuade his own nation that Saturday Night Live is “not funny . . . really bad television!”

Much has been made of the new president’s personality and psyche—his narcissism, his germophobia, his irritability, his minimal sleeping habits, and his reported inability to laugh (though he does smile). In my view, the most revealing personal characteristic of president #45 may be his complete disconnection from the natural world. Here is an individual who grew up in a city, who sees land only in terms of profit potential, who proudly covers the tortured ground with high-rise buildings, who lives in a penthouse, and who walks outdoors only on golf courses. One could make some similar comments about many of his recent predecessors (certainly not Teddy Roosevelt), but in this instance the tendency reaches an extreme.

Donald Trump on his plan for the EPA:

“We’ll be fine with the environment… We can leave a little bit, but you can’t destroy businesses.”

Source: Fox News Sunday, October 17, 2015

How can a person so isolated from natural phenomena hope to understand the vulnerability of our planet’s climate, water, air, and innumerable species to the actions of people (one hastens to add—people much like himself)? How can he appreciate that civilization itself is an organism with a constant need for “food” (not just grain and meat, but energy, minerals, and water as well), that is organized by way of hierarchically ordered and interlinked cycles, and that is subject to natural limits and ultimately to death?

One could argue that all hubris is tied to human beings’ illusion of dominance over nature. Our long withdrawal from wildness surely started with language, which gave us the ability to name and categorize, and thus to psychically control and distance ourselves from what we named; it erupted into alienation with the advent of agriculture, cities, and most recently fossil fuels. But we never stopped depending on the fabric of life in which we have always been entwined. Even as we unravel the ecosphere’s delicate fibers, we draw upon eons of accumulated soil nutrients and minerals, fresh water, and biodiversity.

Life implies death—one’s own mortality above all. Everything has limits. Wisdom resides in the understanding that we are subject to forces we cannot control, and that we must respect and accommodate ourselves to those forces. If we want to have language, farming, cities, and energy, then we must make a deliberate cultural effort to maintain an attitude of individual and collective humility. In practical terms, that means keeping the size of our global population low enough so that it can be supported long-term without eroding natural systems, managing consumption so that resources are not depleted and non-biodegradable wastes do not accumulate, and maintaining checks on wealth inequality.

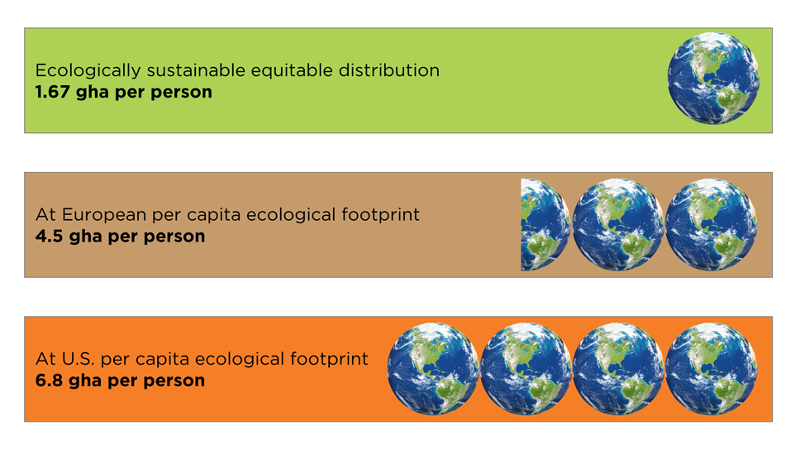

Figure: How many Earths does it take? Productive global hectares (gha) per capita required for the current world population. Data source: Global Footprint Network.

Obviously, we haven’t been doing these things very well, especially in recent decades. The power of fossil fuels fed our collective megalomania. Like people in previous civilizations, we went out on a limb—but modern energy and technology enabled us to go much further than any humans had before. Still, as all civilizations do, ours has reached the point of diminishing returns, of over-reach. Before us lies the senescence and death of a way of living and of seeing the world. Perhaps the new president’s qualities of character are emblematic of these final stages of cultural disintegration.

In the days to come, there will be plenty of opportunities for resistance, protest, and, one hopes, celebration. Inauguration Day 2017 is a turning point; for me, it seems a perfect occasion for a walk in the woods.

Taking your advice and going to the Dickey Ridge Trail in the Shenandoah National Park.

As I have watched the great waves of change building, due to human impact on the natural environment, I characterize the situation as the built-environment which began with the earliest of technologies to build settlements that became cities and founded empires, all taking from the natural environment to make the built-environment of today.

Our financial system has enabled debt to consume the future without care for repayment or maintenance of its productivity. That has been called sustainability and has become a goal, but as the earth graphics show, we are overdrawn on an annual basis, so the cumulative means we’re in a deep hole. We all care more about the built-environment in which we live, than the natural environment we see through the window or from the paved path. It is a backdrop, very out of balance.

Great waves are now in motion which will return nature to a new balance, sustainable on nature’s terms, not humans. American suburban car-cities are not historic city-cities done to serve the human scale of walking, the mobility we are born with. As economies shrink to the available resource base, we can shift to a focus on qualitative rather than quantitative growth. It will not be easy,

To learn about the U.S. post WW-II fear of “urban vulnerability” consider this information. A regional planner from 1973-2008, I did not learn of this history until 2003. Why the low density, automobile dependent suburbs in the U.S.? Urban Vulnerability-Fear of Nuclear Attack led to U.S. Policies to Disperse Population in the 1950’s-Oops, that’s Sprawl